Old Faithful Inn sign, formerly at 1916 East Van Buren.

Phoenix’s Street of Dreams: The Visual Extravaganza that was Van Buren

By Douglas Towne

Many Phoenicians view Van Buren Street as an unremarkable mix of redeveloped sections interspersed with stretches of gritty streetscapes that border on urban blight. The street’s current incarnation, however, masks the former glory of Phoenix’s brightest thoroughfare that served as the “Eastern Gateway” to the city.Although only scattered vestiges of this era remain, Van Buren featured one of America’s most dazzling tourist strips. Motorists were greeted by a seemingly endless succession of enchanting neon signs that employed evocative combinations of names, images and patterns in a myriad of colors. Most signs advertised motels with fanciful themes meant to conjure up historical structures or exotic locales. The motels met travelers’ practical needs for shelter; their faux ambiance also satiated vacationers’ desire for fun and adventure. Van Buren and its resplendent signage defined the Phoenix experience for many visitors. Early auto trails routed through Van Buren, establishing it as the city’s primary automotive corridor in the 1910s.

Businesses flocked to the street to profit from its increasing traffic, which included tourists vacationing in the Valley of the Sun or en route to Southern California. Van Buren acted like a giant funnel that collected most of the cross-country traffic between the Mexican border and Route 66 and routed it 24/7 down the highway.

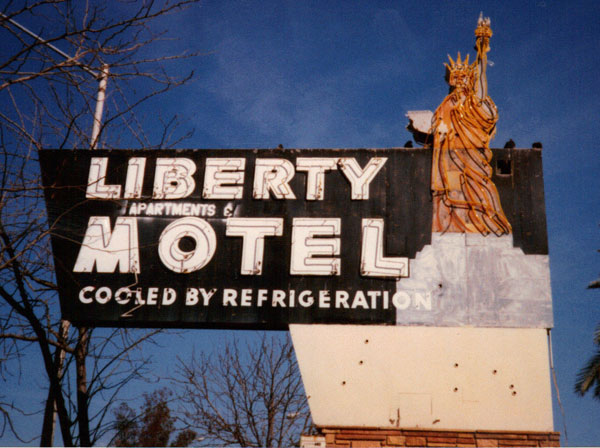

Phoenix billed itself as the “Motel Capital of the World” by the early 1940s, largely based on the density of overnight accommodations along Van Buren. In the span of a just few blocks, travelers could spend the night in motels with neon recreations of Old Faithful, the Statue of Liberty, and the Alamo on their signs. Other roadside lodges featured attractions such as water wheels, putt-putt golf, a 500-bird aviary or posh restaurants. “I remember my family having Thanksgiving dinner in 1963 at the restaurant located at the Rose Bowl Motor Hotel,” Phoenix historian John Jacquemart reminisced, “It was a swank place!”

Liberty Motel sign, formerly at 1903 East Van Buren.

There were also reptile gardens, fruit stands, and curio stores along Van Buren. Amateur uranium prospectors could buy “Nucliometers” and “Geiger Counters” heralding the dawn of the atomic age. At night, tourists and locals alike could watch drive-in movies. “I recall a neon sign along Van Buren of the stunning face of a beautiful lady on the backside of an outdoor movie screen,” said Phoenix native William Linsenmeyer.

Philco TV sign, formerly near 14th Street and Van Buren.

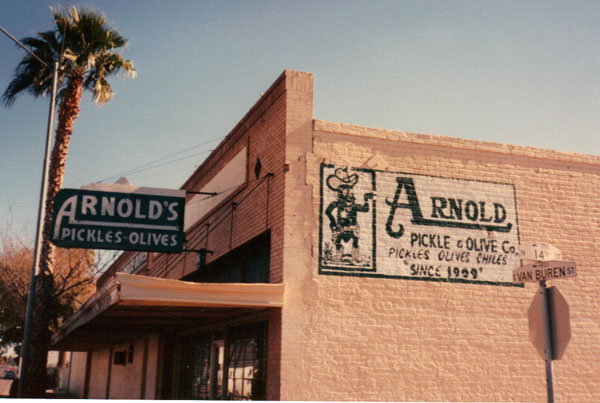

Van Buren even had its own peculiar smell. “My fondest memory is the wonderful aroma of Arnold's Pickles,” recalled Phoenix historian Donna Reiner. “The brine permeated the surrounding neighborhood. Even in the early morning hours it smelled good.”

Arnold’s Pickles sign, formerly at 1401 East Van Buren.

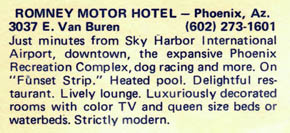

Description from postcard for the Romney Motel formerly at 3037 East Van Buren.

Van Buren’s Early History

The street, named for eighth U.S. President Martin Van Buren, was constructed in the 1870s as the northern border of the Phoenix townsite. The street name changed outside city limits to Tempe Road east of Seventh Street and Yuma Road west of Seventh Avenue by 1895.

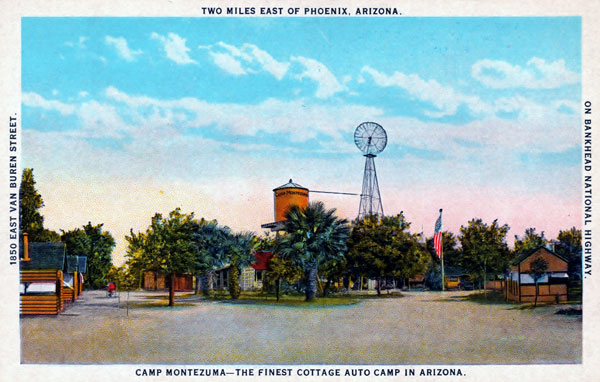

Postcard of the Montezuma Auto Camp at 1850 East Van Buren.

Match book promotion for the “Broadway of America” route.

Van Buren was also along the route of other auto trails including the Atlantic-Pacific Highway, the Borderland Highway, the Old Spanish Trail and the Sunkist Route. Van Buren was officially designated as U.S. Highway 80 and 89 in 1925. The former route was nicknamed the “Broadway of America” and ran from Georgia to San Diego, while the 89 connected Nogales with the Canadian border. Subsequently, Van Buren became a segment of two other major cross-country routes, U.S. Highway 60 and 70 that respectively linked Virginia and North Carolina to Los Angeles. The four U.S. highways overlapped each other for some 60 miles from Florence Junction to Grand Avenue in Phoenix. At that intersection, U.S. 80 split off and continued on Van Buren until turning south on 17th Avenue, eventually reaching Yuma. The other three routes continued northwest on Grand Avenue to Wickenburg.

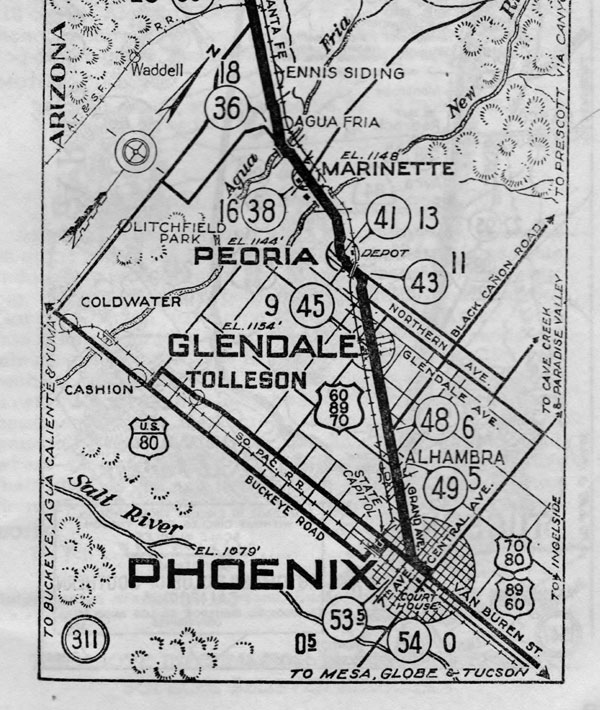

Phoenix map from 1945 Automobile Club of Southern California guide.

Tourist Strip Development

Pioneering auto travelers along Van Buren had limited options for overnight accommodations. Some camped along the road, and others took lodging in formal, expensive downtown hotels. Consequently, auto camps opened along Van Buren. For a nominal fee motorists would pitch their tents and unload their own beds, towels and cookware. Toilets and showers were provided by the campground in a communal building. A municipal auto camp was constructed adjacent to Van Buren at Eastlake Park at 16th Street; private auto camps provided tents supplied with electricity.

Postcard from Camp Joy formerly at 2229 East Van Buren.

Postcard of Minnesota Cottage Court formerly at 5218 East Van Buren.

In the late 1920s, relatively basic stand-alone structures with a bed and stove emerged. Called cabin camps or cottage courts, they typically advertised using painted signs and sometimes featured a gateway over the entrance. By the next decade, overnight accommodations termed “auto”, “motor” or “tourist” courts were built. They usually included a carport or garage between units and morphed into single-story motels with attached units — often in L-shaped or U-shaped layouts with a neon sign along the highway. Phoenix claimed to have the “largest number of tourist courts, cabins and motels of any city in the U.S.,” according to a tourist brochure from 1941.

Postcard of the Sea Breeze Tourist Village located at 2701 East Van Buren.

After a building hiatus caused by World War II, increasingly impressive roadside accommodations cropped up along Van Buren. Travelers were wooed by new amenities such as air conditioning and swimming pools. Van Buren Street had reached its zenith as a tourist strip by the early 1960s. Taking advantage of economies of scale, the later motels were often multi-story structures and affiliated with lodging chains. Hoping gambling would be legalized in Arizona, motels sometimes reserved space in their complexes for potential use as a casino.

Many of the finest motels in the city — along with a support network of restaurants, service stations, bars and tourist attractions — stretched along Van Buren. Every need of the traveler was met; the strip’s future seemed as bright as its neon glow on a summer evening.

Signage Themes and Symbols

At its postwar peak, Van Buren’s motel row was the main artery of Phoenix. As structures dedicated to movement and transience, motels were an apt metaphor for a dynamic city constantly reinventing itself. For travelers with a little imagination, its roadside lodges created an exotic environment for overnight adventures and indelible vacation memories.

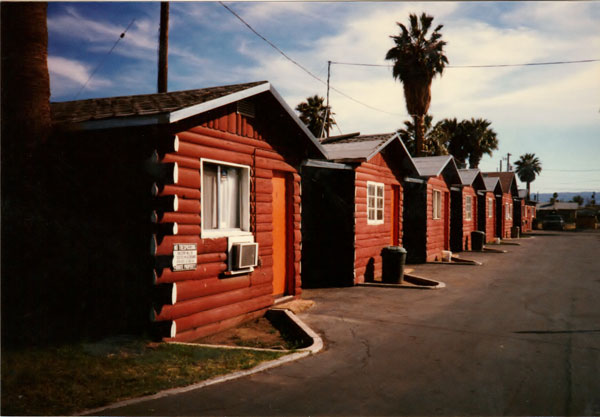

Units of the Log Cabin Motel formerly at 2515 East Van Buren.

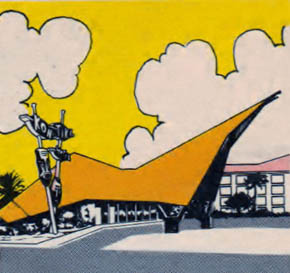

Artist’s depiction of the Kon Tiki Hotel formerly at 2364 East Van Buren.

he Kon Tiki, the last and most impressive independent motel constructed on Van Buren, was a stunning example of Googie architecture with Polynesian flair. It was the motel’s roadside sign, however, that usually attracted passing motorists. Like catchy pop tunes, the neon designs were direct, easy to read and — perhaps most importantly — exciting.

Vanishing Tucson founder Carlos Lozano explained the almost dreamy effect of the signs. "Slowing to appreciate a sign, one becomes pleasantly overwhelmed: one part of the mind is awestruck by the massive scale, another part is dazzled by the profusion of color, while other parts consider form and meaning,” he said. “The overall effect is mesmerizing. Centuries ago, viewing religious figures in stained glass produced the same desired effect.”

Most signs were freestanding rectangular, vertical, or kidney-shaped slabs painted with one-of-a-kind scenes and lettering. In daylight, the signs were multicolored structures. Illuminated at dusk, the buzzing neon tubes created a mystical roadside spectacle. Each sign was a unique piece of commercial folk art.

“I would get up early enough to get wonderful light on places not considered particularly beautiful,” said photographer Steve Weiss of his trips to Van Buren in the early 1980s. “So much of the old signage was hand-painted, with different objects and sculptures from toy cars to giant plastic bunnies. I felt it was like a whole street of ‘outsider art’ made by naive artists whose only intent was to attract the eye.”

Sandman Motel sign, formerly at 2120 West Van Buren.

Many signs along Van Buren were created by prolific designer Glen Guyett, who worked for over 40 years in the Valley starting in 1952. “Every owner wanted their business to stand out and be individually recognizable,” said his daughter Joyce Guyett. “Ideas would be drafted by Glen in the form of a drawing or model to scale and painted to look exactly like the finished product. Everyone loved these creations and they closed many deals. Glen then created the final design and did the math that made the sign sound for wind and stress factors,” Guyett explained. “His influence on Van Buren signage was to bring the newest sign technology to a small Western town with innovative modern ideals. Many early signs around town were created by him; it became the Phoenix style.”

Halls Motel sign formerly at 1925 East Van Buren.

The signage along Van Buren evolved over time. Early accommodations tended to proudly use the last name of the owners, which was often a husband and wife team such as “Halls Motel”. Others were a wordplay on the owner’s name such as Robert Sebree’s Sea Breeze Tourist Village. These motels had neon signs that were often simple, rectangular compositions with the name and the function of the business; glass tubing was used only to outline borders and letters.

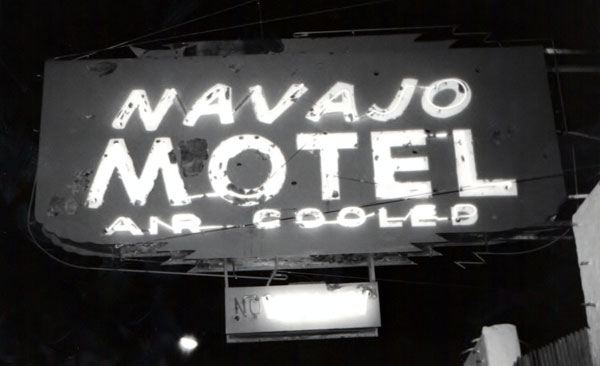

Navajo Motel sign formerly at 3232 East Van Buren.

Sun Villa Motel sign formerly at 2529 East Van Buren.

Popular themes along Van Buren included Mexican/Spanish (Mission Motel), Western (Lazy A Motel), Native American (Navajo Motel), climate (Sun Villa Motel), desert (Dunes Motor Hotel) and upscale or formal (Crest Motel). Surprisingly, many exotic elements were imported from other areas such as the (sic) Cocanut Grove Motel; apparently Phoenix’s native landscape was not glamorous or appealing enough for some visitors. With competition from new, independent chains sprouting in the 1950s, motels along Van Buren radically differentiated themselves with Polynesian themes (Aloha Phoenix Motor Hotel), (Kon Tiki Motor Hotel).

Dunes Motor Hotel sign formerly at 2935 East Van Buren.

Crest Motel sign formerly at 3411 East Van Buren.

Cocanut Grove Motel sign formerly at 2012 West Van Buren.

Match book promotion for the Aloha Phoenix Motor Hotel formerly at 3901 East Van Buren

Match book promotion for the Kon Tiki Motor Hotel formerly at 2364 East Van Buren.

Decline of the Van Buren Strip

The Van Buren tourist strip had begun its downward spiral by the 1970s. Although it still served as the principal business route through Phoenix, construction started on the Maricopa Freeway that would soon allow traffic to bypass Van Buren. New motels — often large, well-financed franchises operated by major corporations — clustered at the freeway exits. Demand decreased for the less accessible Van Buren tourist facilities. Some motels advertised weekly or monthly rates that further hindered their chances of tapping the lucrative tourist trade.

Rose Bowl Motel sign, formerly at 2645 East Van Buren.

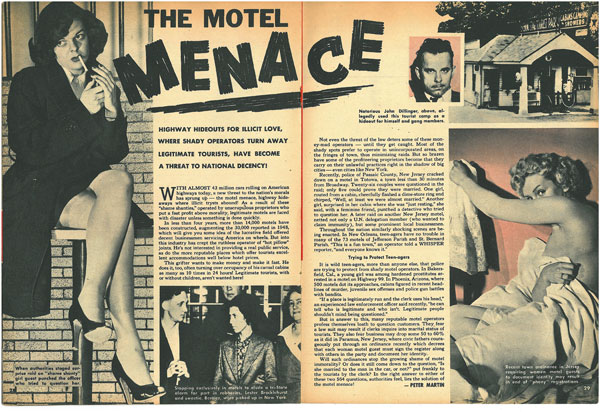

Motel magazine article

Copa Motel sign, formerly at 2834 East Van Buren.

The creeping blight continued as the Papago Freeway was built without an interchange at Van Buren. The street was officially decommissioned as a highway in 1991. The surviving motels reflected the growing effects of crime and poverty: neglected landscapes, abandoned swimming pools filled with dirt, “No Trespassing: Motel Guests Only” warnings and broken neon signs illuminated instead by cheap spotlights. In 2010, despite community preservation efforts, Van Buren lost its most iconic motel with the nighttime destruction of the Log Cabin Motel.

Destruction of the Log Cabin Motel, located at 2515 East Van Buren.

According to local historian John Arthur, of the estimated 150 motels that once existed on East Van Buren only a few vintage motels and their signs remain, such as the Arizona Motel. “If light rail had been routed along Van Buren, undoubtedly more historic businesses could have survived and would be thriving today much like Bill Johnson’s Big Apple Restaurant,” speculated Phoenix preservationist Michael Levine. Levine’s love for neon signage extended to personally rescuing the Sun Villa motel sign the week he saw it come down with no apparent plan for its re-use.

Bill Johnson’s Bill Apple Restaurant sign located at 3757 East Van Buren.

These signs, along with others like the surviving Log Cabin Motel sign, would benefit if Phoenix passed legislation similar to Tucson’s recent Historic Landmark Sign ordinance. The new code allows qualifying signs several options including to temporarily be taken down for restoration, moved to sign corridors and historically accurate signs to be recreated for the original business. Such a program would preserve artifacts from a culturally important era in the development of Phoenix and serve to inspire its residents and visitors.

“There has been resurgence in appreciation for historic signs that is a grassroots movement,” commented Tod Swormstedt, founder of the American Sign Museum in Cincinnati. “They take us back to a time when things were slower. You likely patronized a local mom-and-pop business and its custom neon sign became an icon, unique to your town. This same longing for the old days, and the signs that conjure up the good memories of the past, is what attracts many to historic signs.”

Van Buren’s dazzling collection of midcentury signage that stirred the imagination of generations of travelers has largely vanished. The street’s distinctive historical legacy could have been used as the basis to create a unique, linear redevelopment project. Instead this treasure trove of neon signs was razed to create yet another non-distinct Phoenix streetscape.

Douglas Towne is editor of the Society for Commercial Archeology Journal, the publication of the oldest nationwide organization dedicated to research and conservation of 20th Century commercial buildings and signs. A frequent contributor to Phoenix Magazine, Doug’s articles on roadside history have also been featured in the Journal of Arizona History, Nevada Magazine, IKEA’s Space Magazine and Sign Builders Illustrated. His art, which incorporates roadside imagery and is as much social commentary as it is homage to the past, has been exhibited at galleries including Modified Arts, Tempe Public Library, the Trunk Space, Tohono Chul Park, Phoenix Downtown YMCA and Braggs Pie Factory.