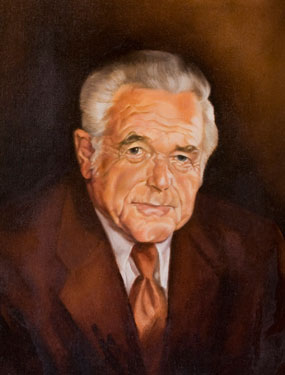

Fred M. Guirey, FAIA A Talent for TransparencyBY WALT LOCKLEY

The house at 300 East Missouri has a strong personality. It wants things. Sheri, the architect’s daughter, says it wants two things. It wants its story to be told, and it wants a party. It wants its story told because the master of this house deserves a better memory. Fred Melville Guirey was connected to the history of Arizona, important and influential for decades, in the first rank of Phoenix architects, author of a long list of familiar buildings, and given the rare honor of an AIA Fellowship in 1969. He was trusted with commissions like Gilbert Olson’s Superlite Block Headquarters and the Art & Architecture complex at Arizona State University, marking him as a professional among professionals. And why does this house want a party? Well, Fred knew how to throw a party. Driven by a sense of beautyGuirey was born in Oakland California in 1908. His father was a railroad conductor, and his mother was a registered nurse who died in a dentist’s chair around 1920. His father moved to Tucson for his asthma. Fred worked his way through UC Berkeley in stages, returning to Arizona to raise money. On one of these trips, in the summer of 1930, he was on the engineering crew that cut the first road from Jacob’s Lake to the North Rim. He earned his architectural degree from Berkeley in 1933. “I think I wanted to be an architect,” he said, “from the time I was three and a half. Don’t ask me why.” After graduation he went to work for the Arizona Highway Department. He married local girl Catherine Bolen, aka “Tat”, on December 28 1939. And started building the original square core of 300 Missouri in a tamarisk grove with his own two hands. He started by building a five-and-a-half ton sandstone fireplace himself, all day and into the darkness of the evening, with Tat running their car for the headlights. This was still the Depression and the fireplace wasn’t to signal stylistic allegiance, wasn’t for curb appeal or resale value, it was for heat. Using his new education he designed and built all the built-in furniture. The result was the first little square contemporary house in Phoenix, and a 400-square-foot Granny house in back for his wife’s parents. Together they looked like a couple of roadside cabins. Guirey spent nine years as a landscape architect for the Highway Department, working his way up from a bushwhacking engineer to director level, an early advocate for native species, and “The Father of our Roadside Rests”. He was a designer at heart, not a born organizer and not motivated by money. There’s a photo of him circa 1946 working in the yard in a sombrero and shirtless under overalls. Sheri says he was never happier than out in the back yard, laying bricks and cursing a purple streak in the air. Primarily driven by a sense of beauty, he had discipline, Depression-era hustle and grit, a phenomenal memory, and high standards for friends and foes alike. Never a negative word about anybody, although he could slyly deflate a pompous ass. Near-strangers would come around and knock on the door and want him to mix their paint, and he’d take thirty minutes and mix their paint. Social Roots, Early HousesYou can’t go far with Guirey without talking about his friendships and the energy he invested into this community. The right word for Guirey’s social life is relentless. A few still recognize his name from that wonderful self-mocking civic organization, the Dons. The Dons was a social club of gentlemen from various strata, from bank presidents to plasterers, who dressed up in black Don coats with big black Don hats, and made their wives dress up like Doñas. Led by Guirey, who became president in 1940, they organized elaborate “Travelcade” adventures and searched for the Treasure of the Lost Dutchman. They roped Harry Truman into their shenanigans at one point. Social connection was obviously smart business for Guirey, but he took a genuine interest in Phoenix, the local history, and community. (Plus he couldn’t say no.) A 32nd-degree Mason, a Shriner, compulsive volunteer, 25 years as the chairman of the Maricopa County Parks Commission (1952-1978), on the board of Goodwill Industries and a dozen other institutions, he was a civic workhorse who made things happen.

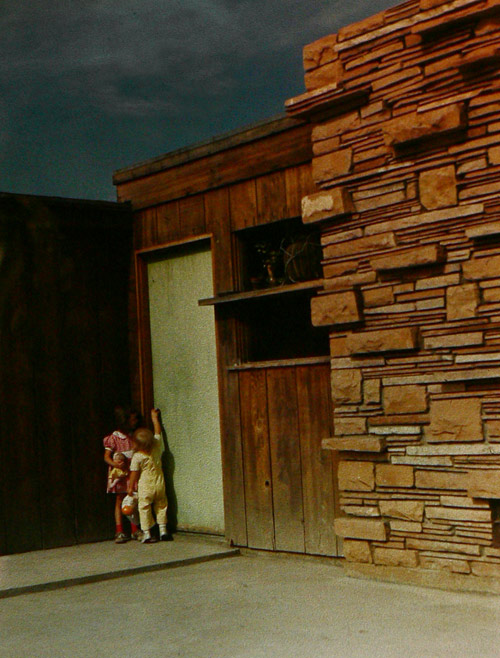

This, too, comes back to the house at 300 E. Missouri. The house was the stage for grand parties, parties like the Mardi Gras with months of preparation. Guests made grand entrances in armor, or feathers, or pearls. The backyard was also happily dressed up as Monte Carlo or Acapulco or wherever. You can still open closet doors and find enough folding tables and chairs for 120 people. Sheri remembers at least one big blowout every month, two or three smaller parties every week. There’s indication that Guirey’s heart was in house design, although his career moved away from it. His favorite commission was a house in Oak Creek. There are, maybe, 15 or 20 houses total. The 1947 Corwin Mocine House may be Guirey’s first “real” commission, and the design shows the familiar Wright residential elements: built-ins, unadorned brick and wood inside and out, the indoor-outdoor relationship, etc. Given Guirey’s education it’s equally likely he’d been influenced by William Wurster and the Bay Regionalists, and their outdoor-oriented, simplified, rustic designs.

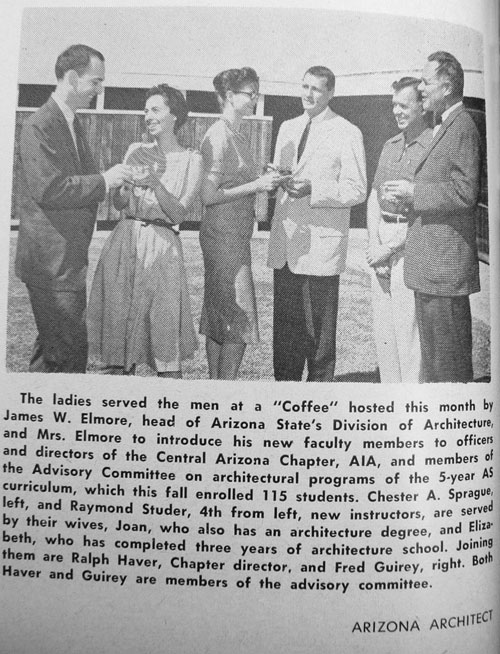

Photo courtesy of Paul Scharf Style Among the StraightsGuirey hit his stride in the 1950s, 1960s, into the 1970s. If Al Beadle and Blaine Drake were Phoenix’s design-build rebels, forever in hot water with the AIA, Fred Guirey was on the other side, among the Straights. Photos show his offices as a collection of IBM-style white shirts and clunky black glasses, buzz cuts, hard thinkers like rocket scientists, bristling with the same atomic-age confidence and competence. We might be attracted to the rebels out of an adolescent urge, but as you age, you know, there’s a clearer value in sticking around and being positive and predictable. In a word, Guirey was a grown-up.

And a Straight in more ways than one. The ASU A&A complex: not a structural curve in sight. The 300 Missouri house: not a structural curve in sight. From his complete known portfolio: very few curves of any kind in sight. I count two out of about 65 major projects. It’s funny that one of the two is a completely circular structure. Guirey wasn’t selling style. Yes, he was among the ten Phoenix architects chosen for the 1961 ASU Alpha Drive fraternity project, but his was the least expensive of this collection and frankly far less interesting than Kemper Goodwin’s or T.S. Montgomery’s or Taliesin Associates’ frats. (All ten of them are now doomed.) And yes, the Republic’s account of Guirey’s career zenith, his 1969 FAIA induction ceremony in Chicago, praises him, but it was the left-handed-complement of his firm being “known for its careful construction practices.” Connected at Every PointLook longer, and his career is strongly connected to the legacy of mid-century Phoenix architecture at every point. To hit the highlights: If you measure your historic Phoenix architects by their presence on Architect’s Row, then check out 506 East Camelback from around 1952, now an accountant’s office. It’s a taut, spare building, shaped and positioned as if keeping an eye on Al Beadle across the street.

If you’re looking for the pure modernist swank, yup, you got it. The waffle-roofed steel-frame three-story 444 West Camelback of about 1963 was Guirey’s. The curtain walls here are entirely of glass and porcelainized steel sheets, sandwiches of insulation between interior and exterior metal surfaces, slotted into aluminum frames. They’ve proven durable, though like a tin drum inside when the wind blows, and swank if you ask me, with two sister buildings next door and up on north Central.

The same technique of glass, aluminum and insulated porcelain panels in aluminum frames was used at the $4M, 10-story Coronet Apartment Hotel at Central and Roosevelt from 1962. Herman Chanen boasted that “This will be the fastest a 10-story building has ever been built in Phoenix.” The Coronet had a great location and each room’s windows were angled so the entire building surface was glassy and faceted. Coffee shop and retail at the base, three penthouses at the top, by 1974 the Coronet was a Ramada property and in 1988 it was stripped to its skeleton to produce the glass box standing there now.

The commission with the deepest roots with the modernist community is Gilbert Olson’s Superlite Block Headquarters, at the northeast corner of 7th Street and Colter, now a school. Of course it features Olson’s product, “vertical-stack-bond blocks, set in steel frames,” in a pattern specially developed for this structure. The cornice fascia and a two-story porch have been lopped off since, and some benighted creature has removed the shade on the south face and installed... windows. Still it says something important about Guirey that Olson chose him over all other Phoenix architects.

Patterned concrete block is a Phoenix mid-century design signature, and Guirey prescribed generous doses of it as privacy screens at the Doctors Hospital (20th and Thomas, now obliterated), put acres of suspended brise-soleils with an exotic oriental twist at APS Headquarters up in Deer Valley, used it intelligently at the Greenwood Mausoleum at the end of open-air corridors to poignant effect, and elsewhere.

For Phoenix modernist branch bank fans, there’s a perfectly decent Valley National Bank in Holbrook, but a more exciting, high-quality 1970 Western Savings branch in Sun City which is sort of Prairie Brutalism, with a handsome oxidized-copper roof over chunky concrete and black glass. Churches? There are a couple, but in 1981 Guirey said, “I gave up doing church work years ago... Most ministers are frustrated architects. And their wives are frustrated interior designers. Between the two, they have all the answers.” From the era of concrete shell structures, Guirey’s firm designed the Phoenix Memorial Stadium in 1962 with a large 12-unit concrete paraboloid shell roof looming over the seats -- an extraordinarily daring move. The contractual back-and-forth with the city on this job led to a lawsuit which GSAS ultimately won. Finally, if we’re being honest, we can’t make too much of the firm’s involvement in the Valley National Bank’s Valley Center, now the Chase Tower, 1967, the tallest building in the state. GSAS was the local associate firm of Welton Becket out of southern California, who made the design decisions. So the banquet was eaten in L.A., and the dishes were done in Phoenix. Curey, Spinky & ArnoldJust to layer in the resume, Guirey had left the Arizona Highway Department in 1942. He entered into private practice in Arizona in 1946. He joined Stan Quist in partnership that same year, until Quist’s death. From 1947 through 1950 he was partners with Hugh Jones; from 1950 through 1960 Guirey practiced on his own. They reorganized as Guirey, Srnka & Arnold in 1961, then added Sprinkle on top as partner in 1965. Sprinkle had managed the very active Flagstaff satellite office. Seventy people in the firm at one point. People tended to screw up their name. “Curey, Spinky & Arnold” is my favorite. Two heart attacks restricted his ability to work, and in 1981 Mr. Guirey was eased out of his own practice. He seemed restless and uncomfortable at home, set out to pasture. Suddenly, it was all over: George Sprinkle died of a brain tumor in 1980. There was a fire in the office in June 1982. Richard Arnold died in September 1982. The firm was merged into the Los Angeles firm Daniel, Mann, Johnson & Mendenhall, and Guirey’s name disappeared from the profession. He died in 1984. He and Tat had been married for 45 years.  Back to the HouseAs he did, towards the end, let’s circle back to the house. It’s a generous house, set at an angle on an expansive lot. Mr. Guirey’s original modest square was expanded twice, the front bedroom and the sunroom added in 1950, and a more ambitious expansion in 1963. Step inside, and there’s the huge sandstone chimney that in 1944 fronted Missouri. The house unfolds in successive squares, an insistently one-story experience set out on a grid, but with modulations in ceiling height and floor depth, strips of daylight overhead, and centered around that massive hearth.

All that wood? All those beams? You’re looking at redwood. (After a recent storm, when Tat was still alive, a tree fell and destroyed part of an exterior fence. Tat insisted on replacing redwood with redwood, at $600 a board.) A few more steps inside, and you’re practically outside again. Blurring the line between inside and outside is part of the standard playbook, and there’s a lot of glass and an interesting balance of solids and voids, but that’s not the secret that snaps this design into focus. It’s oriented towards the 40-year-old garden of an old-school landscape architect, but that’s not the key either. You might guess that the mid-Century Asian decorative theme relates to the Japanese-ish detailing of the shed and the Granny house, and the overall Zen feeling of the garden, and maybe the whole house was laid out on a tatami module?

Nope. There’s one fact that entirely explains 300 E. Missouri. It was built for parties. The traffic flows, the patio zones, the multiple living rooms, the sightlines through the glass, all calculated for a hundred laughing, talking, drinking, flirting people, showing up, showing off, telling elaborate jokes with their hands, and maybe enjoying two or three fistfights later in the evening. This kitchen was born to pump out appetizers. And that’s why the house is so big. “It’s too damn big,” the caretaker says, not only because she has to clean it, but because it’s just a lot of walking. She says it’s a ranch house—it’s a ranch and a house. And the only tangible remnant of an entire vanished social scene. It’s rare that one house so reflects the personality and values of its designer. This is him. If Fred Guirey could speak, he would want people in the house, he’d want a party. And he’d want his story told. Mr. Guirey, with our complements, here it is. ResourcesInterview with Sheri Tingey, March 6, 2009

Phoenix Magazine, November 1981

Selected Commissions1944 Guirey Residence at 300 Missouri, expanded 1950, expanded 1963 1947 Corwin Mocine House 1952 Whitacre Residence Circa 1952, 506 West Camelback, his architectural office 1954 Greenwood Garden Mausoleum expansion, 2300 West Van Buren Street 1954 Camelback High School, 24th Street and Camelback (razed) 1957, Reynolds Residence Circa 1960 Superlite Block building, 7th Street and Colter Circa 1960, Hibiscus Apartments, Phoenix, 5250 North 20th Street, 37 units (designed by Murray Harris) circa 1960, 444 West Camelback, for developer Arnold Becker Circa 1961, 400 West Camelback, for developer Arnold Becker, next door and 18 months after 444 West Camelback (Murray Harris, designer) 1961 fraternity on Alpha Drive, ASU's Greek Row (to be razed) 1961 APS Headquarters, 21st Avenue and Cheryl, site of the old Paradise Valley airport 1962, Coronet Apartment Hotel, 1001 North Central, Central and Roosevelt (designed by Murray Harris; radically modified 1988) 1963 Phoenix Municipal Stadium Circa 1965, North Congregational Church, Glendale & 7th Avenue (modified) Circa 1966, the Center for Planetary Research, Lowell Observatory, Mars Hill, Flagstaff, winner of the AIA Design Award for 1967 1966 remodel of the Christown VNB 1966, site plan and residences for the Colonia Miramonte, 30 acres adjacent to the Camelback Inn 1968, site plan and library for the American Institute for Foreign Trade, now the Thunderbird School of Global Management Circa 1968, Valley National Bank branch, 1st and Hopi Streets, Holbrook 1970 the three-building Art and Architecture complex at ASU 1970 Western Savings in Sun City, 10743 Grand Avenue, Sun City Multiple buildings at NAU in Flagstaff, including 1971 Liberal Arts Building, 1971 High Rise Dormitories #1 and #2, Women's Dormitory "K", 1971 Library-Study Center, 1973 Physical Education-Recreation Bldg 1972 Valley Center (now Chase Tower, as local associate of Welton Becket) 1973 New Resurrection Mausoleum, Oak and 48th Street 1975 the circular Maricopa County Juvenile Court, 3131 W Durango Street 1980 Park Central Mall renovation Find out more about Fred Guirey, FAIA

|