Alfred Newman Beadle, Architect: The Steel and Glass Man

Alfred Newman Beadle, Architect: The Steel and Glass Man

First published in Carefree Enterprise, September 1988.

Copyright 1988 By Gene Garrison

Author of There's Something About Cave Creek: It's the People (2006)

He answers the phone with a no-nonsense, state-your-case, "Beadle."

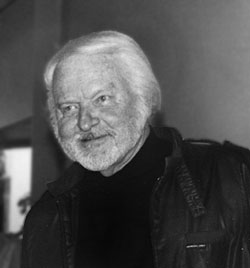

Sixtyish, bearded, white-haired—there's something about the man that says presence, power and determination.

There's a Beadle look, in his person it's a black shirt, white pants and white boots. In his architecture it's a contemporary statement consisting of elegance in line and color.

About a year ago he and his wife, Nancy, bought a duplex on Carefree Drive between two condos. He has been remodeling it ever since, transforming it into a residence. Even the kitchen is elegant - sleek, practical, track-lighted and done in dove colors. He expects the work to be completed soon an apologizes for the "war zone" look. He quickly explains that the structure is not his style of architecture, but a redesign of an existing building. It's definitely Beadle, nevertheless, with its graceful curved walls, planes and simplicity of line.

"Nancy and I purchased this place for two reasons - we didn't want to by a lot and build without knowing the community for at least a year or two, and I want to be a suburban-urbanite. It's zoned R-5 so I'm going to office here."

Al Beadle has been in architecture for forty years, having spent all but two years of that time in Phoenix. He has designed high-rise building there as well as being the out-of-town expert for buildings in Salt Lake City, Chicago, San Diego and Los Angeles.

"I was thirty-two years old when I designed by first twenty-two story building" - The Executive Towers in downtown Phoenix at Second Street and Clarendon. This was quite an accomplishment at that age, probably a record.

He has never stopped being impressive. His design awards and international reputation for design excellence have earned him an inclusion in Who's Who in America, Who's Who in the World, exhibits in the Museum of Modern Art in New York and soon the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

McGraw Hill recently published a book entitled 25 Years of Record Houses, the best 50 houses of the last 25 years. "I was floored to be included," he says. "It featured a house I built in the 'sixties. There were only four selected west of the Mississippi. This may add to my credentials, or it may not."

"I've been through the wars. By choice all my clientèle are in the private sector. A proposed major development takes forever for approvals (unlike governmental buildings which require no approvals from anyone) and everyone gets a shot at you. Someone always has a pencil on your drawings. We all know about the camel - a horse designed by a committee. I just had to give it up. The stress is horrendous and the rewards are disappointing.:

"We made a decision to move to Carefree ten years ago, but it took nine years to accomplish it. We have done some houses here for friends in Desert Ranch and up in the Highlands. My problem is I have a reputation. I have a palette of my own materials. I'm known as the steel and glass man. I won't deviate from that too much. People come to me saying they want a Beadle house. Now I may have to adjust the palette."

The word palette, as he uses it, means the materials he employs and the way he uses them to create his own architectural statement.

"I would not hesitate at all to say that Carefree has lousy architecture. I can make my point by referencing the new shopping center. Carefree deserved better design."

When he refers to Santa Fe architecture as "mud huts" my eyebrows shoot up. "you don't like Santa Fe?"

"I like Santa Fe when its done by an expert—not Santa Fe done by an amateur. For instance, Bill Tull, who has built in the area, is absolutely superb in that style. It's not necessarily the architecture, but the marriage between the environment and the building. It's not my style and I couldn't at my time in life and reputation live in a Bill Tull House."

This indicates that his commitment to contemporary design is so strong that he feels he cannot go in another direction without betraying the philosophy on which he built his career.

As Beadle says that it's almost impossible to describe architecture, he reaches for a page of Le Corbusier quotations and reads:

You employ stone, wood and concrete, and with these materials you build houses and palaces. That is construction. Ingenuity is at work.

But suddenly you touch my heart, you do me good, I am happy and I say, "This is beautiful." That is Architecture. Art enters in.

My house is practical. I thank you, as I might thank Railway engineers, or the Telephone service. You have not touched my heart.

But suppose that walls rise toward heaven in such a way that I am moved. I perceive your intentions. Your mood has been gentle, brutal, charming or noble.

Beadle continues, adding his own feelings about Architecture with a capital A. "It has to be done in some extremity, either simple extremity, or, if you're going to build a Santa Fe house it has to be done in the extremity that a Santa Fe house was intended to be. It's kind of brutal. It's the kind of house that you never sweep. All of a sudden people are building Santa Fe style houses and bringing in housekeepers. It was a type of ranch house where ranch-hands lived. It absolutely astounds me the way people want to build mud huts and drive a Mercedes to their offices. They ought to ride horses to their offices. They ought to be consistent."

Every once in a while he emphasizes a point by slamming a fist on the desk.

Beadle brings Tull's name into the conversation again. "If there's a design-minded person like Bill Tull in control there is no fear of the neighborhood. It's the fear of the owner being in control of the architect. Chances are, a good architect will walk away from an owner if he intends to violate the community."

He says that the founders and early developers of Carefree has a great idea, and he knew some of them twenty-five years ago, "but I think it's just gone. Architects Joe Won and Hudson Benedict (who designed Rusty Lyon's house) had a design reputation and were doing good things here. The International Restaurant (designed by Joe Wong), somewhere under the tile roof of the Diet Center, had class. Somewhere the ideology waned and it was lost. It's impossible to look at Carefree with a mediocre viewpoint, but mediocrity has entered. Carefree to me is like a desert beach town - Malibu - and should be respected as a unique community. Its buildings should be inhabited sculptures as the community founders envisioned. Art was a buzzword then. Maybe I can help revive it and not be offensive." He jokes about the possibility of being run out of town and, after hearing the comments on the "mud huts" I envision such a thing - his white hair blowing in the wind as he takes off at high speed in his yellow Cadillac convertible. But, nah, he wouldn't run. Anyone who has met him knows that.

He chuckles about what he calls "Carefree's Serfs and Rulers situation," and adds that he has no trouble speaking his mind. "When there's an injustice being done, my cohorts will come and drag Beadle and push him up front and say, 'Get 'em, Al. Get 'em." And he does.

He has principles. He insists that he is not in architecture for the money, but because it is so spiritually rewarding. "Fred Osmon and some other architect friends of mine said that being a good architect is a damned curse because you can't give it up. You almost apologize for sending clients a bill. You're so rewarded by just having them commission you."

"When you do a residence for someone, you never know who is going to be the best-suited for that house in the next thirty or fifty years. There might be ten owners and sooner or later someone is going to come along and feel that spirit and he has to have the house. That's uplifting."

It's Beadle's opinion that great architecture has a very small market. "My own houses have always been extremely severe. I believe that simplicity taken to an extreme is elegance. I totally believe that. It's too easy to say, 'Let's put in a little of this and a little of that,' like a stew."

He mentions trendiness and I compare the green shag carpeting and avocado appliances of the early 'seventies to the arabesque stained-glass windows that many builders are incorporating into their houses today. It is my opinion that these windows will date a house in ten years, just as the shag carpeting and avocado appliances are doing now. They are simply trendy.

He burst forth with one of his opinions: "Unfortunately, most people are not aware of good design. The architect's catch-22 is that people with taste have no money, and the people with money have no taste, so that often leaves the architect out."

He softens his judgment on taste. "How could a lay person who has not spent his entire life in architecture not know what he likes? People can, however, distinguish what they don't like."

The absolute rule of the desert is low-profile, quite a contrast to his high-rise city buildings. "Anybody building a two- or three-story building just to get bragging rights has violated the community. This is a two-story building, but I'm surrounded by two-story buildings, if you think I'm being hypocritical here." It would look inappropriate to have a one-story building dwarfed by two tall ones.

His low-profile concept means a flat roof. "I will not violate the community by putting up a pitched roof, especially with red tiles. You know what God did to Pompeii. He got so sick of looking at red roof-tiles that the city vanished. All they had to build with was that clay - not the wonderful materials we have now. Low profile is my number-one priority. I will berm it into the site to get it as low as possible. Sometimes I have a problem because I also want to be as high as possible to get the views. I want to be sympathetic to people looking over and at the house. We did that in the Highlands. We have a house on top of a knoll, but we sculpted it right into the hillside so that we do not violate anyone. One thing I will not do is molest a site. I will not push a rock or move a tree. Yes, I'll make a contrasting statement from nature to architecture, but it will be such a delightful contrast that it won't violate it. I'm extremely sensitive that way, even though I've been more active along busy urban streets such as State Street in Chicago - but they have the same problems there."

Al Beadle has been around. He was in the Seabees before he was legally old enough to join, worked in construction and considers himself a "hard-hat architect". He's not afraid to get dirty. He has hands-on involvement with his structures.

You can be sure that the Beadle influence will be felt in Carefree. "If I am fortunate enough to do work in Carefree and environs, I assure you that I will not cause visual pollution. It will be visual excitement or I will not be involved! Nancy and I both want to contribute to the community, not take away from it."

In his efforts, he may ruffle feathers - but he doesn't care. He doesn't even mind being called a curmudgeon!