A Tale of Two Fingado Houses

Early years with a young Al Beadle in the 1950s

If you know anything about Midcentury Modernism, or have heard of Masters of the Southwest, then you have surely seen the name Alfred Newman Beadle, the architect who started his career in Phoenix in 1951.

Beadle was born September 23, 1927 in St. Paul, Minnesota. He learned construction from his father, who built kitchens for hotels and restaurants. He also received training in construction during World War II as a Seabee. He built two houses in Minnesota before he moved to Phoenix in 1951. Beadle designed and built a variety of commercial and residential projects over the years, numbering well over 200 at the latest count.

Al Beadle was known as an uncompromising architect who embraced International Style modern architecture. He designed austere modular “Beadle Boxes” with floor to ceiling glass walls. Oh, what Al conjured up inside those glass boxes. He was a consummate magician. But instead of conjuring a rabbit out of a hat, he drew the outside in.

He developed his style throughout the sixties, seventies, up into the nineties, when he was being compared to Neutra, Mies van der Rohe, Oscar Niemayer, Corbusier and others. Beadle brought the geometric symmetry of his glass boxes to the harsh climate of the Sonoran Desert and allowed the barren desert to create magnificent vistas for his clients’ enjoyment.

Being Right

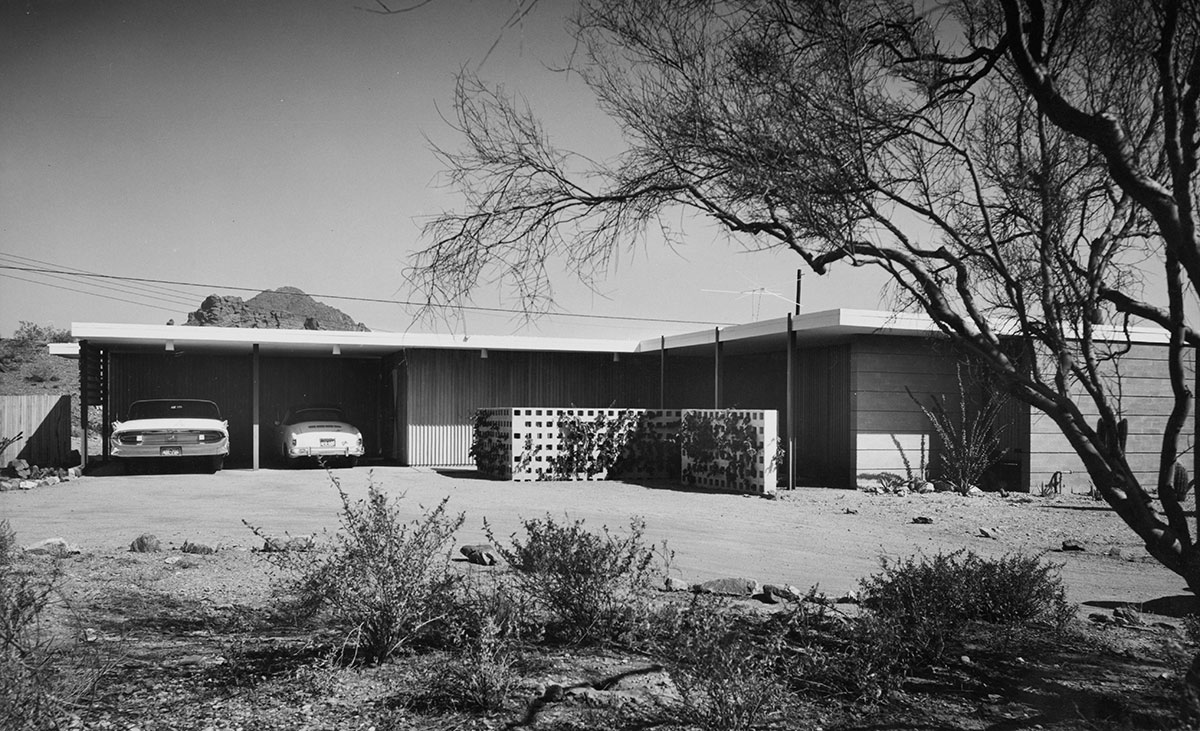

I believe our house in 1952 was either the very first Al had a commission for, or was at least one of the very first. It was certainly one of the early midcentury moderns that are so sought after today.

I’ve researched all of the numbered Beadle houses and our first home at 3515 E. Stanford Dr. isn’t listed. The numbers assigned to Beadle houses when the book Constructions was written only included homes whose location and provenance was certain. A decade has passed since the 2008 edition was published and more homes continue to emerge. Our first home would have been numbered between 5 and 6. Our second home was built in 1957, placing it somewhere between 10 and 11.

Fingado House #2 in 2012, five years before its demolition

Fingado House #2 in 2012, five years before its demolition

The story of our first home will come as news to Beadlemania followers. This is also the story of our friendship and respect for one of the most interesting people we ever knew.

But there is not a single concept of which I am convinced that it will stand firm, and I feel uncertain whether I am in general on the right track.

I don’t want to be right, I only want to know whether I am right.”

~Al Beadle

I'd like to believe that it meant more to Al when Fritz and I came back to him in 1958 to tell him that some people from California wanted to buy our first house; it wasn’t for sale, they’d just driven by and liked it. But we told Al we wouldn’t sell it until he assured us that he would build a second one. That expression of confidence and admiration of his talent gave Al the confirmation he sought. He was right.

Even after he was published widely and recognized internationally, Beadle never felt that he could rest on his laurels. Al was included in the Case Study Program in Arts and Architecture Magazine and the Architectural Record Houses of the Year. His works are part of the permanent collection of New York’s Museum of Modern Art.

So how did we make the connection with Al? How did we form our mutual admiration society? I often reflect on how Fate or Destiny (whatever you believe in) plays a part in the direction our lives take.

Fate steps in

We moved to Phoenix from Texas in 1952 when my husband Fritz was assigned to manage the first Carrier Corporation office and introduce refrigerated air conditioning to the Valley of the Sun. Up until then, Arizona had done pretty well with the ubiquitous swamp cooler, a machine that allowed water to drip off fibrous pads with a fan blowing the cooled, moist air through a house. It was called evaporative cooling.

But with the coming of Carrier, the age of true air conditioning became the preferred living environment in arid, hot conditions. It was destined to succeed, even though it was far more expensive than the evaporative coolers.We rented a casita in a guest lodge (as resort-motels were called back then) and arranged for a realtor, Mary Helen McGuinn of Russ Lyon Realty, to drive us around Phoenix looking at houses. We were getting a bit disheartened. Nothing captured our imagination until she drove by a small modern house which had a Sold sign stuck on the For Sale sign.

When we told her that that was exactly what we were looking for, Mary Helen arranged for us to meet the designer Al Beadle. We met with him in his studio/residence on Royal Palm where he lived with his wife Nancy and their two children. This was in 1952, the year after they moved to Phoenix.

The Foundation

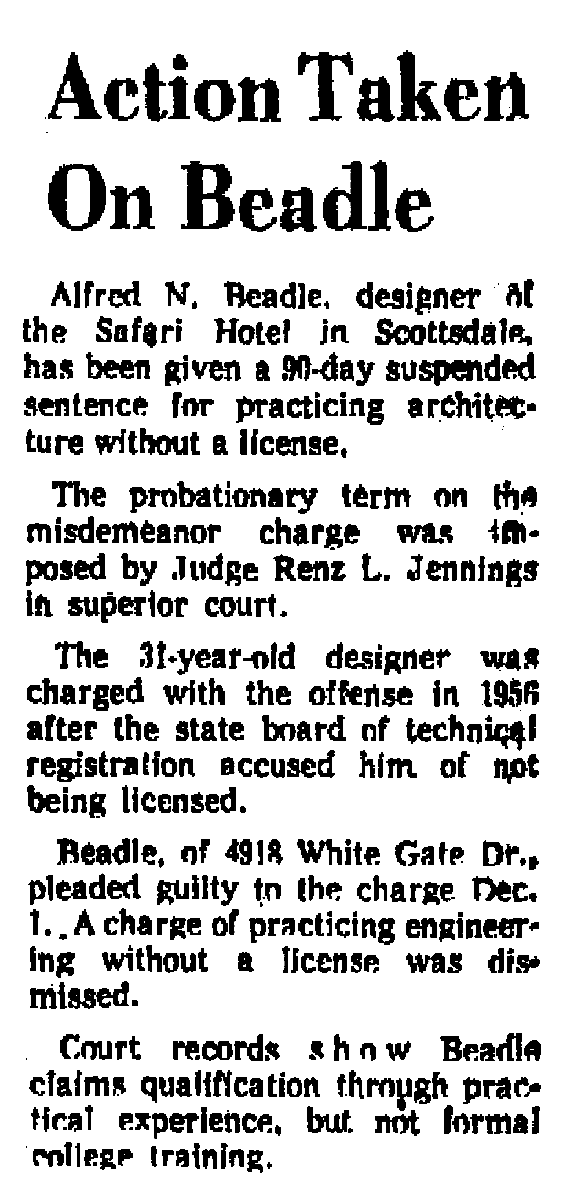

Al called himself a Designer because he didn’t have an architectural license at that time. That didn’t bother us, because all we were interested in was getting an ultra-modern house built.

Fritz was brought up in Spain and Germany. Normally he would have preferred a more traditional approach to architecture. But he had spent the middle 30s in Weimar at the engineering school, and had become acquainted with the Bauhaus era in Weimar, where the prevailing theme was Form Follows Function.

Barcelona Pavilion by Hans Peter Schaefer CC-BY-SA-3.0, Wikimedia Commons

Barcelona Pavilion by Hans Peter Schaefer CC-BY-SA-3.0, Wikimedia CommonsHe had also been an interpreter for the Germans at the strikingly different German Pavilion at the 1929 World’s Fair in Barcelona: a glass box, which featured ultra-modern furniture by Mies van der Rohe, Wassily Kandinsky, Oscar Niemeyer and others of Bauhaus fame.

We liked Al immediately. He was only 25 but so sure of himself, confident that he could design something we would like. I’m inclined to think that Fritz’s association with the Bauhaus era was a deciding factor: that we would be able to think “outside of the box” while agreeing to ultimately live in one.

I think Al also held the belief that the transcendental experience of walking into a building driven not solely by function, but by form as well, led to his philosophy of “Architecture is inhabited sculpture.” We left that first visit with the conviction that this young man would make a name in architecture, but never imagined that it would loom so large, or that we would play a role in it.

Judge Rawghlie Clement Stanford

Judge Rawghlie Clement Stanford

The Concept

Our realtor Mary Helen lost a sale, but we gained a friend when we asked Al to design our home. While driving around Phoenix looking for a piece of land we saw an elderly gentleman wearing a black suit, white shirt and black string tie hammering a For Sale sign on a lot on Stanford Drive. It had a magnificent view of Camelback Mountain and the Praying Monk. He told us the acre would cost $1500 and handed us his card.

That was our introduction to old Judge Stanford, the former Governor of Arizona and Chief Justice of the Arizona Supreme Court in 1952. There were no houses on Stanford Drive, but it was on the northern side of the Arizona Canal just east of 32nd Street, after crossing the bridge over the canal.

The concept of building a modern house in that barren landscape intrigued us. We purchased the lot from Gov. Stanford and in the process met his son and family who later became close friends. Our house would be located across the street from the Hermosa Inn, a popular winter resort in the fifties that had been built around the large home of Lon Magargie, a famous artist. It still exists and was recently named one of the Best Hotels in the United States.

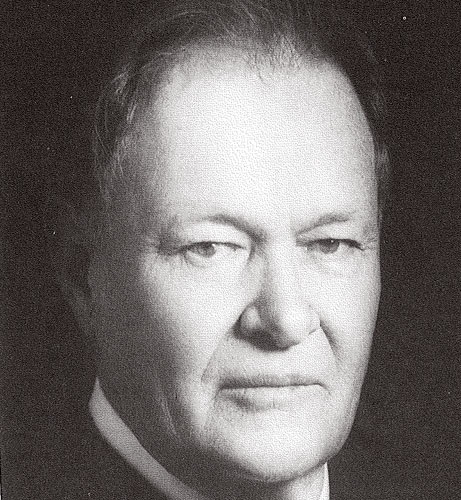

A young Al Beadle

A young Al Beadle

To find out what we liked and didn’t like, Al suggested that we drive to Palm Springs for a weekend. Al had a friend who owned a swimming pool company and if we were discreet we would be able to get into some of the VIP grounds to examine the construction up close.

It didn’t take much to convince us. I salivated to think that we would be inside the grounds of the likes of Bob Hope, Dean Martin and Frank Sinatra. So with Fritz driving, Al in the passenger seat and our daughter Marta and me in back, we drove to Palm Springs.

It didn’t materialize the way we had planned. His friend was out of town that weekend so we drove around looking at all the modern houses, without knowing who lived inside. Al took notes of our comments. On the way back to Phoenix, he organized his thoughts and got details of our needs.

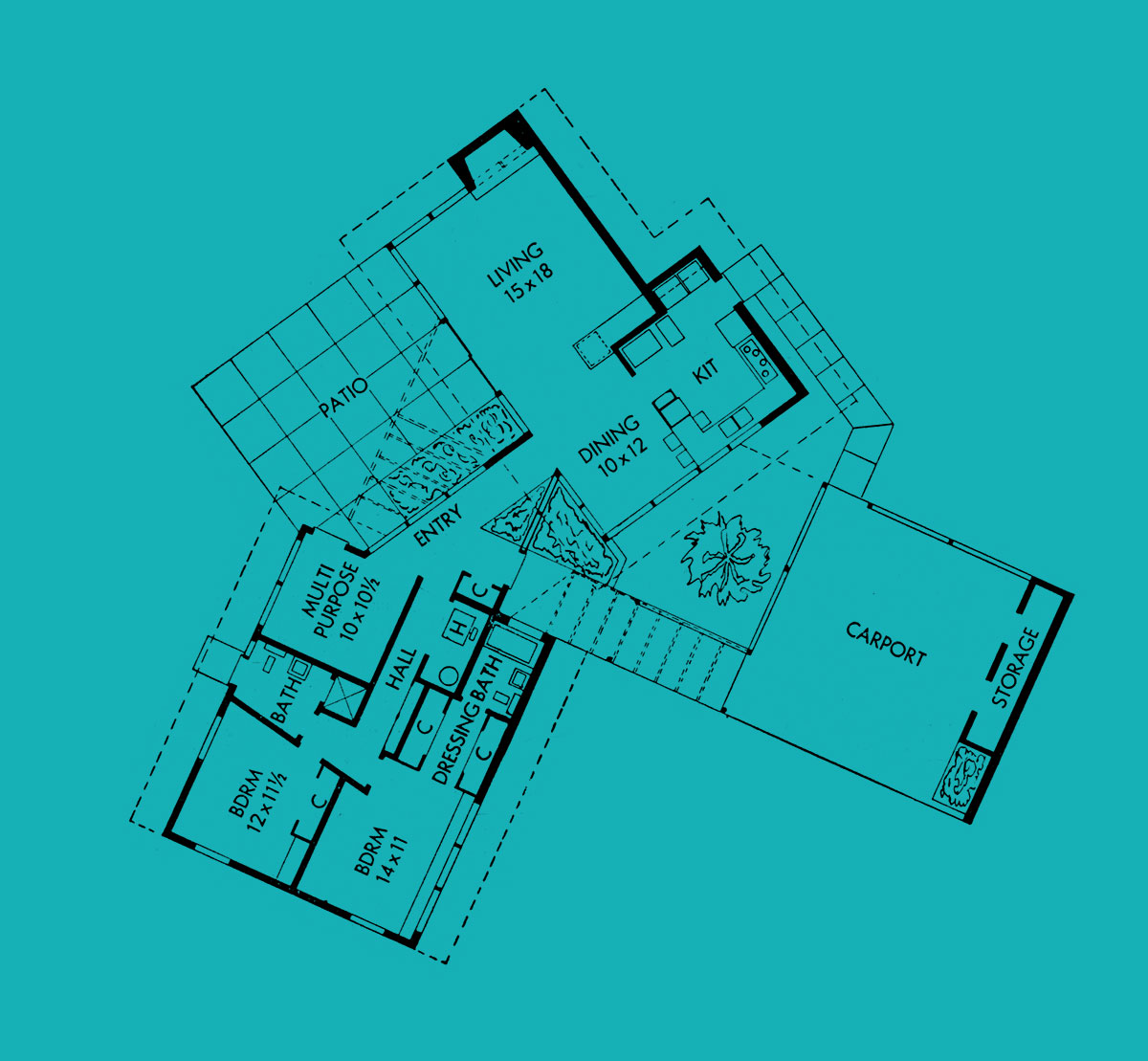

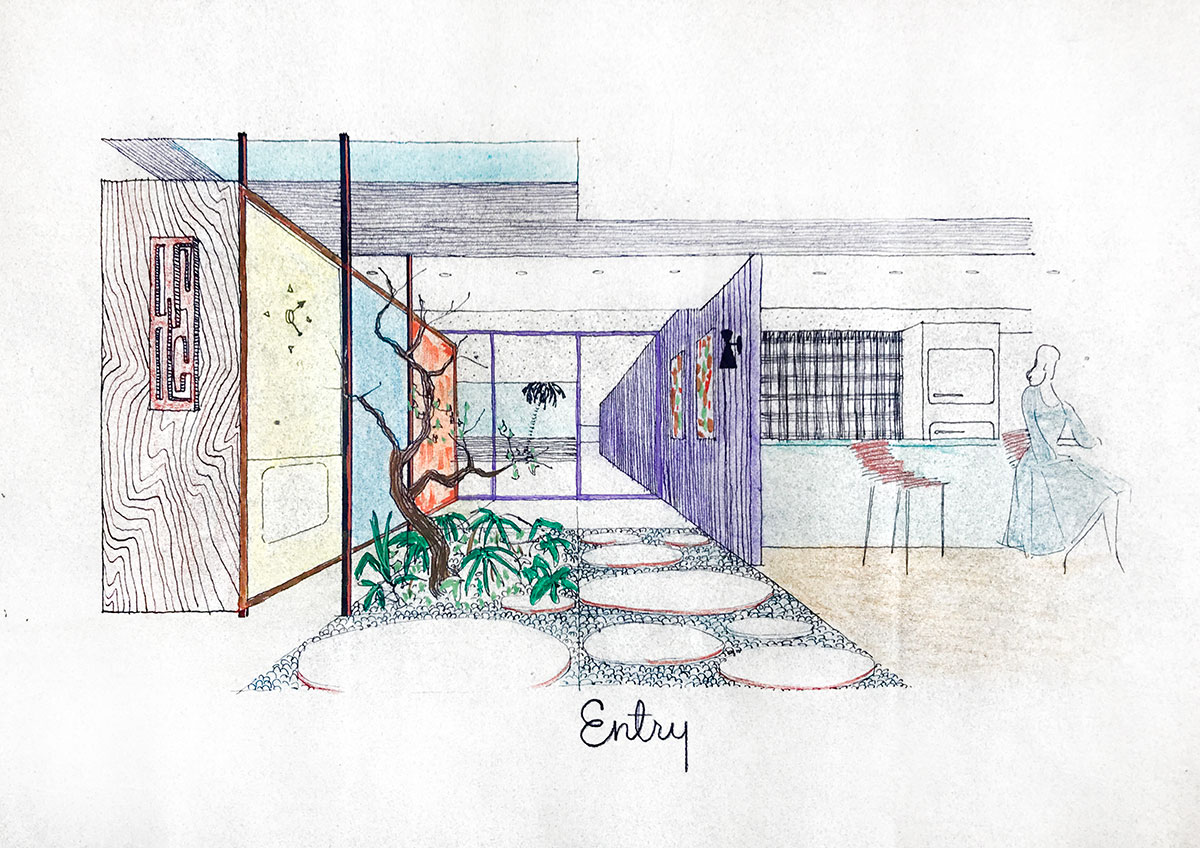

He came up with a floor plan of a house with a walkway from the freestanding carport to a completely glassed-in entry, with a triangular planting area next to the front door. A glass wall extended your view to the back patio and Camelback Mountain.

A rectangular box which contained two bedrooms, two bathrooms, and a triangular-shaped den were on the left. The tiled entryway took you on the right to the second rectangular box, angling off in the opposite direction. This contained the dining room, kitchen, and living room with a walled fireplace at the far end.

All the walls facing Camelback (living room, entry and den) featured floor to ceiling glass. We were stunned with Al’s vision of what could be done with our acre lot and the magnificent picture windows we would have.

The Compromises

Looking over his floorplan we soon discovered that there was not much negotiating possible to accommodate Fritz’s mandate to conserve air conditioning costs and Al's desire to have walls of glass. When Fritz told Al to change the full windows in our daughter’s bedroom because they faced west, to my utter astonishment Al just turned to Fritz and said, “Fritz, you're the mechanical engineer, but I’m the architect.” It was the first time I had ever seen anyone have the guts to tell Fritz off.

They compromised to a certain extent. Fritz conceded that the west wall was the only one that could have windows in Marta’s bedroom; Al changed them to clerestory windows and they were both satisfied. I think they each thought he had “won.” That was when their mutual respect for each other grew.

In the rest of the house, Al had his way with floor to ceiling glass walls. Fritz even spent an extra $600 for a 5-ton heat pump rather than the 3-ton that would have been sufficient for the 1350 square foot house. And he willingly paid $120 for the extra electricity the five months of summer, which worked out to $25/ month.

Let’s pause here for a moment for a quiet chuckle at those prices, keeping in mind this was 1952. Fritz justified it to his Carrier colleagues: everything else was oriented to the east. Fingado House #1 cost about $15,000 to build; with the acre of land it came in well under $20,000.

What a dismal way to go through life, working for money.”

~Al Beadle

Al always had the greatest integrity when it came to pricing his work. Granted that he was just starting out and didn’t have a “name” for which to charge extra, but he was the same way many years later. He loved designing with a passion but wanted his homes to be affordable to everyone. He warned ASU students against selling out.

The Astonishing Colors

Al painted the outside of our house Palo Verde Green and inside, painted the exposed ductwork in the dining-room ceiling Ocotillo Red. (Can you imagine a staid engineer allowing Al to paint the air-conditioning ducts orangey-red? Fritz thought it looked great.) The doors were painted yellow, inside and out. Back in 1952, (as is today, unfortunately) houses were painted beige, beige, and more beige, so Al’s playful ways with bright colors was innovative and not universally accepted.

The house featured a cantilevered cabinet with sliding pegboard doors, which Al designed for us, between the living room and the kitchen to hold the television and the Hi-Fi.  Pegboard was just coming into its own then, but without all the little hanging features. It was also used as the doors in our kitchen cabinets.

Pegboard was just coming into its own then, but without all the little hanging features. It was also used as the doors in our kitchen cabinets.

I made all of the furniture pieces with the larger legs from kits that we ordered from a Danish company in New York. The couch and chairs were by Knoll and Eames.

I made all of the furniture pieces with the larger legs from kits that we ordered from a Danish company in New York. The couch and chairs were by Knoll and Eames.

We moved into the house in early 1953 and at our Open House cocktail party I had silkscreened paper cocktail napkins with a miniaturized floorplan of the house. While nibbling on some hors d’hoevres Al commented on the interesting geometric design on the napkins. I smiled at him and said, “Look closer, Al.” The expression on his face as he suddenly realized it was his floorplan was incredible. He grabbed a handful of napkins and walked around the room delightedly showing everyone what I had done. I think he was very touched by it.

We moved into the house in early 1953 and at our Open House cocktail party I had silkscreened paper cocktail napkins with a miniaturized floorplan of the house. While nibbling on some hors d’hoevres Al commented on the interesting geometric design on the napkins. I smiled at him and said, “Look closer, Al.” The expression on his face as he suddenly realized it was his floorplan was incredible. He grabbed a handful of napkins and walked around the room delightedly showing everyone what I had done. I think he was very touched by it.

We lived there from 1953 to 1957, loving our unusual little home. The house soon garnered attention. One Saturday we found a note on the front door asking if we would consider selling. The people were from California; they had to have it, and the purchase was completed in two weeks. You might wonder why we agreed so quickly. Well, they offered us $26,000 and we thought we’d made a fantastic deal. Almost 30 years later we saw our Stanford Drive house pictured in a real estate magazine for $277,000!

But more importantly, Al said that as soon as we found the land he would design another house for us.

The Affirmation

We bought another acre lot from the Stanfords on nearby 38th Place. The cost reflected the burgeoning value of the area as more houses sprang up: $3,000. Al came to assess the views from our raw desert plot; we have a photo of him turning in all directions holding his hands, fingers squared to form a frame, up to his eyes to get the “pictures” framed and to integrate the huge 150-year-old Saguaro cactus near the entrance into his design.

Being higher, this land had all the lights of Phoenix as the main vista; Camelback and the Praying Monk could be be seen behind the house. It was one hillock and wash before Senator Goldwater’s property, with a tall antenna attesting to his interest in short wave.

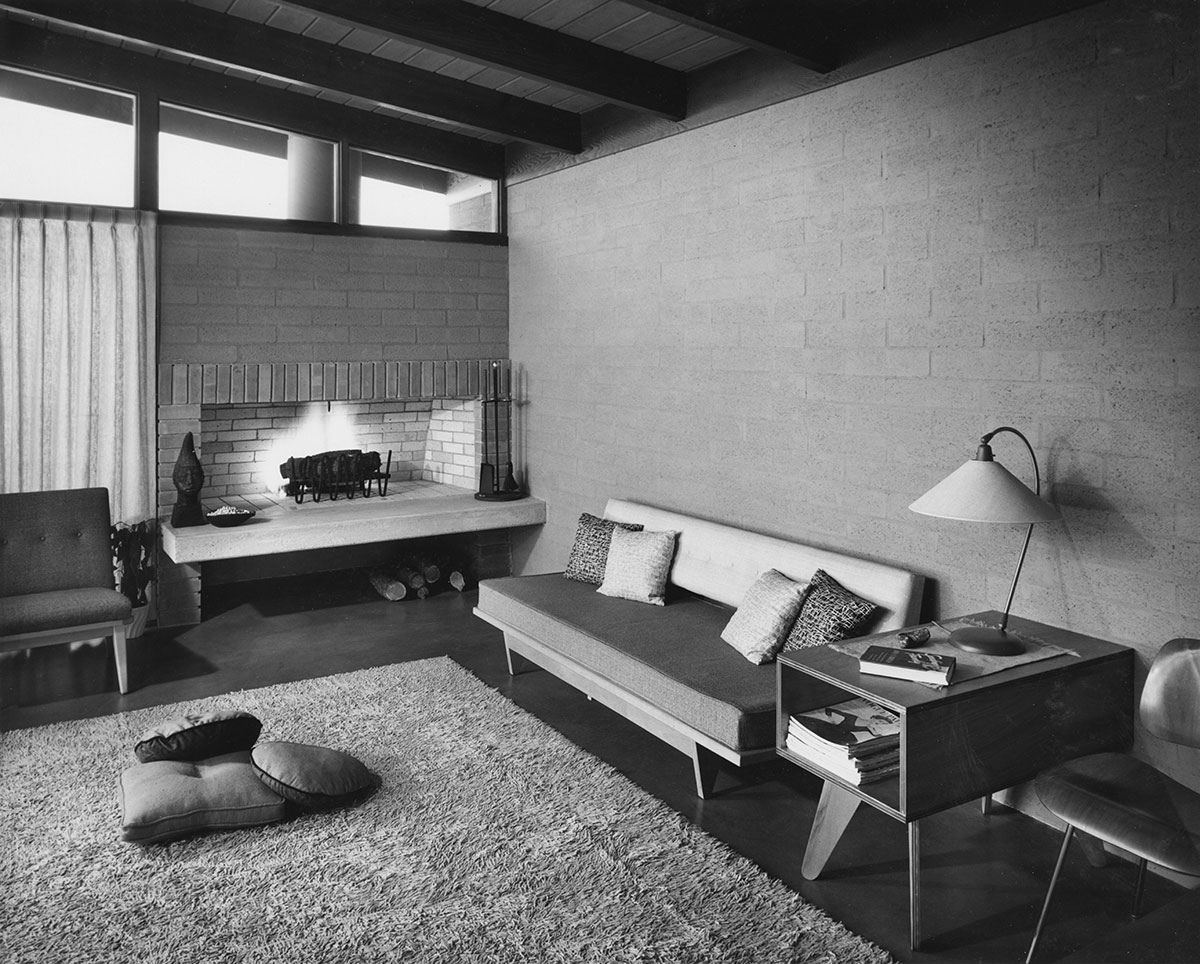

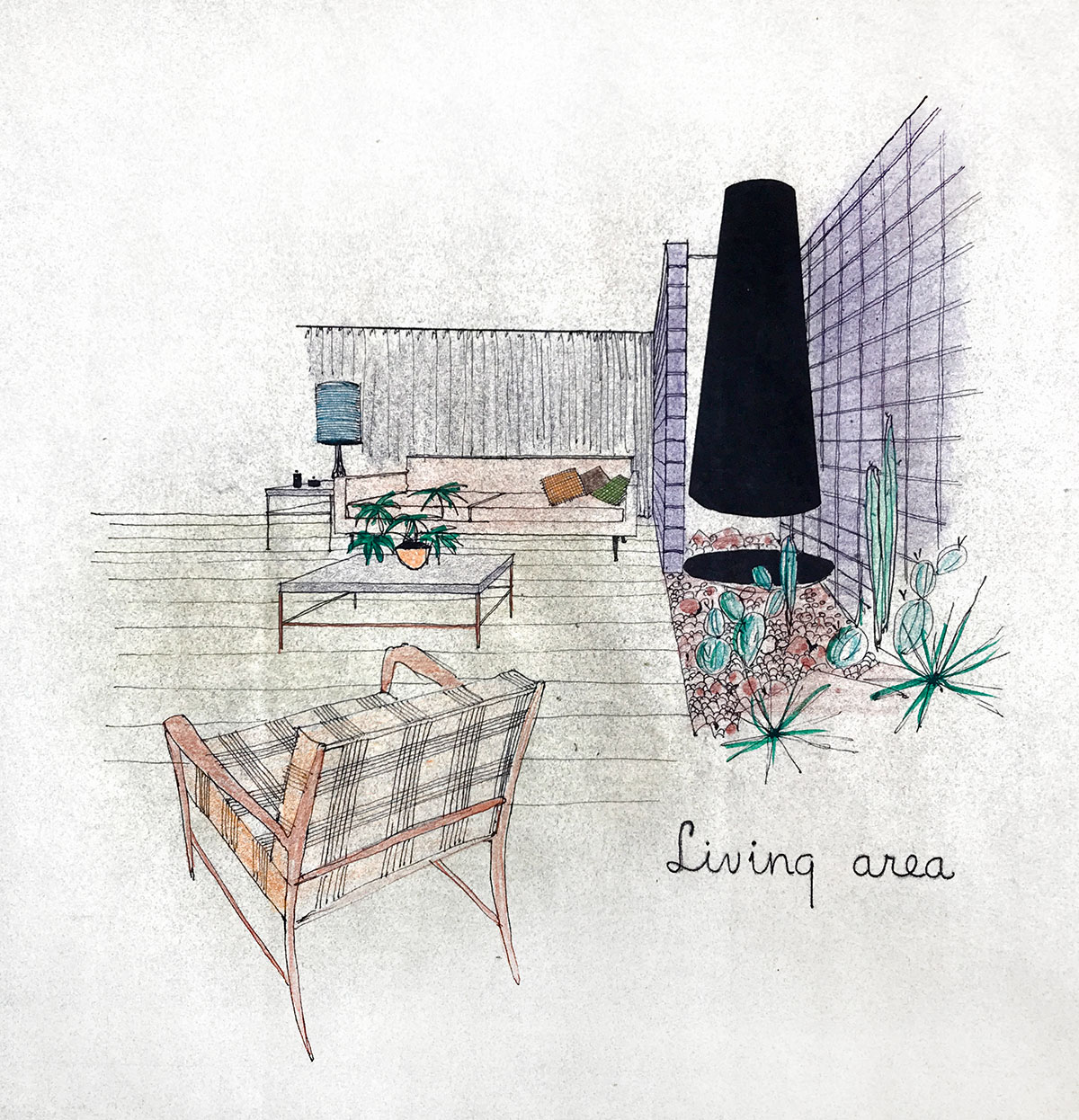

The result was another spectacular small Beadle house and was, I believe, the first Beadle Box. It was designed in 1957 and we moved in before Christmas. The 6001 38th Place house was one of his early rectangular boxes with full glass walls on both sides, similar to his own on White Gates Drive of the same era, which later became Al’s trademark. This house was a bit larger than the first, at 1500 square feet.

Outside, the pumice block walls were painted mauve, a shade of soft purple, with unique redwood-slatted walls in other areas. Al washed the redwood with a white glaze, which had the effect of turning it a soft purple color that matched the block walls but added texture and form.

Each two-inch slat was reversed—one laid flat, then one protruding—it had the effect of louvers and created shade on the walls where it was introduced. This made a big difference in the air conditioning requirements which Fritz thought was brilliant.

Fritz and Al had formed a mutual admiration society, while each maintained their beliefs that everything was okay as long as it was done his way. Yes, Al was prickly; he was also stern, gruff, arbitrary, stubborn, adamant, surly and I can think of other adjectives. You either did it his way or you could get another architect. But it boiled down to: why would you want to do it any other way, when his way was so right?

A custom freestanding TV and Hi-Fi cabinet partitioned the living room from the entry, appearing to float between its metal posts. Al painted the four sliding doors white, orange, mauve, and milk chocolate. Both doors in the carport were painted with triangles of orange and white, a motif used on his own home on White Gates. I think Al secretly appreciated us not questioning his unusual choice of colors.

Even with carpeting: when the cement was poured for the entrance walkway Al embedded a large round slab of wood in the wet cement. He removed it after the cement dried, to form an indentation in front of the glass sliding-door entry. This would become the embedded doormat.

The entry inside had gold color carpet with large circles cut out to conform to the shape of the planter in the middle of the entry floor, using the same slab of wood for size. The gold circles that had been cut out were then used as the doormats. Same size circles were then cut out of cream and chocolate-brown carpet and stitched in the holes. The carpet-layers were terrified as they stitched them in by hand, but the circles fitted perfectly. And how imaginative!

We didn’t require an interior decorator because Al just planned it all; he was the whole enchilada. Nancy once confided to an interviewer that she let Al choose all her gowns because he had unerring taste.

Though daughter Gerri Beadle reports that her father had a fear of color in his later years, he sure didn't in the 1950s. We found it interesting that Al had painted the Uhlmann House (1955) and the Safari Hotel (1956) with hues of pink and purple as well.

Our master bath had turquoise mosaic tiles on the island surface and mustard yellow for the floor. The island contained two opposing sinks with a sliding mirrored cabinet built over it. Picture how spacious it would be in the mornings with two people getting ready for the day, one on one side of the island and the other across from him and the same amount of space for the two sinks next to each other. Each person had their own sliding mirror cabinet for their toiletries. So efficient!

In the patio outside the master bath, Al embedded metal frame circles in the hard desert floor, poured cement into them and added river-polished pebbles on the top, for stepping stones. We sun-bathed out there in walled-in privacy.

The guesthouse at the end of the carport was welcoming: large living-sleeping area with a couch that became a sofa bed, furniture, large bathroom, but no kitchen.

When we expressed our pleasure with it, Al merely nodded, saying dryly, “You build it, they will come.” Yes, we became a popular destination vacation. Come January, February, Carrier people in Syracuse suddenly found it necessary to take air-conditioning surveys. Fritz kept an Honor Roll in his office for the ones who actually came in July.

The mauve walls inspired us to order our annual Christmas tree spray-painted lavender with silver sparkles, and with modern Austrian decorations. It received many compliments.

We always enjoyed listening to the initial comments of our guests as they entered, upon seeing the colors of the Hi-Fi cabinet and the carpet circles: It was either “Love it!” Or: “How...interesting.”

At our Open House-cum-Christmas party in1957 Al and Nancy presented us with a beautiful mosaic coffee table that Al had made himself. It was made with Italian black mosaic tiles with a rectangular insert of yellow tiles from the bathroom floor. It went beautifully with all the Knoll furniture and Eames chair.

A black metal cone fireplace designed by Al was placed at the end of the living room in a bed of cacti with windows on each side so that it appeared that the desert flowed through the living room.

It broke my heart to see photos of this very house, listed for sale in 2004 for $1.2 million, and saw how subsequent owners had destroyed every bit of Al’s artistic creativity; they removed the cone fireplace, closed off the windows at each side and had turned it into a closed-in niche. They’d removed the fascinating room divider with the colorful sliding doors, filled in the planter, and removed the circled carpeting, replacing the entire area with just an open floor plan with solid color carpet. Later it was tiled.

I learned recently that Al was known to recognize when his architecture had been altered too badly and would have said, “Bah, let them destroy it; it has already been destroyed!”

In 2017 this house suffered a fire in the kitchen, was sold, and the new owner razed the entire building. A Beadle masterpiece lost forever to another megamansion.

I’m so happy to donate all the photos of the original construction along with Al’s personal colored-pencil drawings of the house as he envisioned and we faithfully fulfilled it. Its image lives on in the Beadle Archive.

The Disillusionment

When Fritz joined the international division of Carrier and we moved to Zürich, Switzerland in 1965, we sold Fingado House #2 for $34,000. Twenty years later, it was listed for $330,000. Then in 2004, $1.2 million!

We left the States to live abroad for 44 years. Al’s homes were selling well, he was getting recognized and he was able to indulge in his passion of creating what he could be proud of. He was designing houses, restaurants, hotels, and commercial buildings.

But some of the attention he was getting was not good: a wary local architectural profession began to hound Beadle about practicing architecture without a license in 1958. They didn’t like that he was getting so much commercial business. He had built the famous Safari Hotel in Scottsdale by then and the American Institute of Architects was bitterly opposed to professionals engaging in design-build.

Al was in trouble. He continued his work, but did not use the word architect for himself. He was taken to court where his lawyer made the point that Frank Lloyd Wright was also practicing architecture in Arizona without a license. Wright ultimately received his license. The profession pressed their case; Al lost. The defeat shook him; it was a blow from which he never totally recovered. When other professionals don’t like your work, it’s one thing. But when your peers reject you, it’s crushing. He became deeply depressed, not knowing where to turn.

He got a call from Alan Dailey, the man whom he later claimed “saved my life.” Dailey was a respected East Coast architect who had retired to Phoenix. He offered to lend his name and credentials to a partnership with the young designer. (In an article about Fingado House #2, Alan Dailey is mentioned as the architect.) In that way, Al could keep on practicing until he had accrued enough apprenticeship hours to sit for the architectural registration exams, which he passed with flying colors. From the late 1960’s to the 1970’s success followed success, earning Al national attention for his work. Al became one of only a handful of Phoenix-based architects to achieve national status.

But the lawsuit left him bitter. When we visited him and Nancy in Carefree in the nineties, he told us about what had happened: his struggles with local authorities and their stifling permit regulations. We could hear and feel his frustration with authority. But he refused to be cowed and went on to build many houses in the Phoenix and Scottsdale area, which are often pictured in articles today showing examples of midcentury modern architecture.

The Result

Nancy wrote us a note on April 29th, 1999, when we were living in Kelowna, British Columbia, thanking us for our letter of sympathy after we learned of Al’s death from liver failure on October 10, 1998. She and her daughter Gerri continue the difficult task of organizing all the information that arrives about Al for the archives at Arizona State University.

Author Janice Fingado

Author Janice Fingado

We were perhaps some of the few of Al’s clients for whom he made color-pencil renderings of both houses. I’m grateful to donate them along with the original floor plans and the photos of the furnished houses as they were when we lived in them.

It should add greatly to the recognition of this principled man who only lived to design affordable homes for those individuals for whom good architecture would change their lives.

As I look around my present house in Tucson, and see the Barcelona Chair, the Kandinsky chair, the openness of the light-filled rooms, the minimalistic decorating with my own abstract paintings, the Feng Shui views to the outside, making it a part of the inside, and the quiet pleasure of my studio where I create nature’s stones into beautiful pieces of jewelry, I know that this quest for perfection was instilled in me by Al. Now it is ingrained in me; I can live no other way.

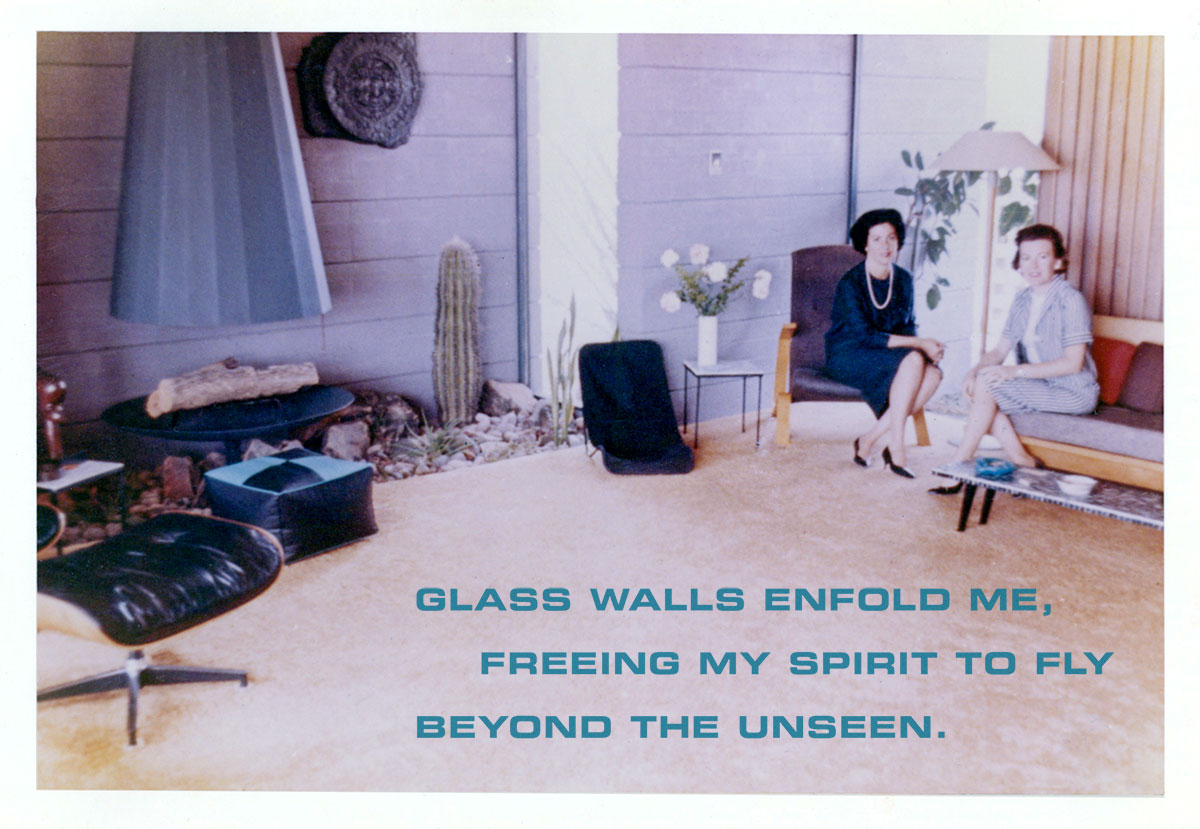

Glass walls enfold me,

freeing my spirit to fly

beyond the unseen.

A Haiku poem I wrote about living in a Beadle Box.

I think Al would have understood.

Bibliography

- Sunset Magazine. October, 1954. Hi-Fi center featured.

- "Let's Have a Fire Tonight...", Sunset Magazine, November, 1954. Fireplace featured.

- “Quality and Comfort in the Desert”, House & Home, November, 1954.

- Around Your Home, Tucson Daily Citizen, July 9, 1955. Cover story.

- Around Your Home, Tucson Daily Citizen, July 16, 1955. Continuation of previous week's story.

- “Harness your Hopes to a Plan”, The Perfect Home, November, 1955.

- Annual Better Homes and Gardens Building Ideas,1956.

- "Arizona’s Famous Modernist Al Beadle", City AZ, November 1999. Special Collectors Edition 13-page tribute to Al Beadle.

- Homes and Gardening Section, Arizona Daily Star, August 2, 1959

- Architectural Digest magazine featured the fireplace, date unknown.